Table of contents

Introduction to Open Innovation

- Definition of Open Innovation

- What is the difference between Open and Closed innovation?

- Who introduced Open Innovation?

- Which company uses Open Innovation?

What are the types of open innovation?

Internal Open Innovation vs. External Open Innovation

The differences between Inbound, Outbound and Coupled Open Innovation

Why do we need Open Innovation?

How to implement Open Innovation?

- What is an open innovation strategy?

- What is an open innovation platform?

- Best practices to enable open innovation

Introduction

Remember Boaty McBoatface?

In March 2016, the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) launched an online competition to determine the name of its newest research vessel. The ship was meant to join the British Antarctic Survey and the organizers therefore hoped to receive a raft of lofty suggestions suitable for the grand ambitions of the NERC.

Instead, they got Boaty McBoatface. In a sign of the times, the British public did not hesitate to lampoon the NERC’s overly posh aspirations. The name Boaty McBoatface won the popular vote by a landslide and the NERC now had a public relations crisis on its hands. They could not possibly accept a name as silly as Boaty McBoatface for their expensive vessel, but they also knew that in a country simmering with populist sentiment on the eve of the Brexit referendum, the general public would not like it if their choice was overruled by the NERC’s leadership.

Fortunately for the NERC, then science minister Jo Johnson managed to save the day by naming the boat after national treasure Sir David Attenborough. For good measure, the name Boaty McBoatface was recycled for one of the remotely controlled submersibles on board of the RRS Sir David Attenborough.

Submersible Boaty McBoatface started its maiden voyage on the 3rd of April 2017.

Now that five years have passed, this incident seemed like a perfect introduction to the fascinating power (and glorious pitfalls) of what experts in the field like to call Open Innovation.

The Open Innovation methodology promises a lot of opportunities for advancement but can also be difficult to navigate. At SteepConsult, we understand that in such a situation, good guides are everything.

Without Virgil, Dante had never been able to reach Paradise after all. Over the course of this guide we will cover all the ins-and outs of the topic which are important for practitioners and thus support you in building your own Open Innovation paradise.

It is often said that wisdom begins with the definition of terms. By defining terms, we are able to categorize items based on their relevance to our challenge. In other words, by defining terms we equip ourselves with the focus needed to tackle complex issues.

This is particularly challenging in the context of innovation, where the old Facebook motto “move fast and break things” still exerts a romantic pull on many fledgling innovators. Failing to properly define concepts and procedures can be a costly mistake to make however and we would therefore like to help you avoid this common pitfall. We have already written an article on the differences between innovation and invention, so in the next paragraphs we will focus on the correct definitions of open innovation in particular.

What is open innovation?

Definition of Open Innovation

According to Henry Chesbrough, the Berkely Haas professor who first coined the term back in 2003, the Open Innovation paradigm assumes:

DefinitionThat firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to market, as the firms look to advance their technology.

Open Innovation therefore takes an expansive view of the innovation process in contrast with more traditional methodologies. It emphasizes cooperation, transparency, and pragmatic thinking in the sourcing of ideas.

On first glance, this is not so different from older approaches which also seek to promote these traits, but traditional methodologies seek only to promote these traits within the boundaries of their own firm.

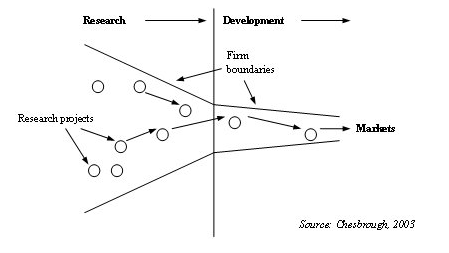

The traditional view as described in Chesbrough’s 2003 book

Open Innovation is more inclusive, as it seeks to involve external parties in the innovation process. As can be seen when comparing the figure below with the figure representing the traditional view, this inclusivity increases both the number and strength of the interactions throughout the innovation process.

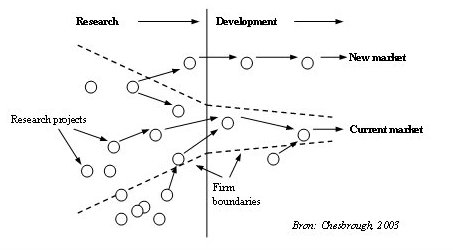

Open Innovation as described in Chesbrough’s 2003 book

While this increases complexity, open innovation also provides a more diverse set of methods to anchor knowledge within an organization. If done right, the absorptive capacity of a firm is enhanced right at the moment when more ideas present itself through the various interactions with the world outside of the confines of the traditional R&D department.

What is the difference between Open and Closed innovation?

As stated earlier, in stark contrast with more traditional closed-system innovation, Chesbrough and his disciples argue that enterprises in Open Innovation systems do not keep their innovation efforts restricted to their internal R&D departments.

Firms using this Open Innovation approach seek to involve other areas of their business and even outside parties in the innovation process. This does not mean that these firms outsource their R&D efforts. They remain active participants in the process and the R&D departments’ traditional role is not so much diluted as it is becoming more focused on capturing value. Either by internal development like before or by laying claim to some of the value created by R&D efforts outside of the organization.

In the wickedly complex world that we live in, this approach allows Open Innovation firms to attract valuable insights and methodologies from outside of the firm. By working together, different approaches and expertise are blended together to reveal insights that the narrower view of the traditional closed-system approach would never be able to cover.

Who introduced open innovation?

The guru of the Open Innovation movement is the aforementioned prof. Henry Chesbrough, but many other influential voices have added to the debate and research about Open Innovation over the years.

Other interesting people to follow are prof. Joel West, prof. Wim Vanhaverbeke, prof. Martin Curley, prof. Ward Ooms and many others. Aside from individual researchers, there are also several big corporations which have experimented with Open Innovation over the years.

Which company uses open innovation?

The list below is non-exhaustive, and the successes and failures of the included companies will be discussed more in depth in the paragraphs to come when their experience is illustrative for the concepts and approaches under discussion:

- Philips

- P&G

- Pfizer

- Unilever

- Apple

- Nokia

- Lego

- Netflix

- L’Oréal

- Total Energies

- Tesla

- Panasonic

The increasing number of firms leveraging open innovation to create value is a testament to the developments we have underwent as a society. Innovation has never been as crucial for success as it is today, but at the same time the people organizations need to realize their innovative potential have never been more empowered.

While the Great Resignation that came about during the CoVID pandemic was unprecedented in scale, the mobility of highly educated workers had been on the rise for several decades. Pockets of knowledge now exist well outside of the research laboratories of large enterprises and have drastically broadened geographically as well. These alternative clusters are often more appealing to skilled staff members than a purely corporate existence.

Investing in Open Innovation allows traditional organizations to access this knowledge, but it is also a hedge against the departure of key workers. Before the trend in Open Innovation came under steam, such a loss could prove critical to innovation programmes, causing many years of delay. Through being more flexible about in-and outsourcing knowledge however, this risk is now much easier to mitigate against.

Another important aspect has been the development of new sources of capital. In particular, the rise in venture capital activities has been significant over the past two decades. Now that everyone seems eager to put their money to work, it has become much easier for firms to e.g., spin out promising products into new enterprises that are better able to respond to market forces.

What are the types of open innovation?

Open Innovation is a multi-faceted concept. It is therefore possible to divide it further into many different subcategories, depending on the dimension that is in focus.

The proliferation of terminology has contributed to a veritable Babylonian confusion within the field of innovation.

For a layperson, it is not easy to get a grip on the subtleties that separate one dimension of open innovation from one of the others.

The most important of these subdivisions shall be discussed in this paragraph, so that we have a proper understanding of the complexities involved.

Internal open innovation vs. external open innovation

A first relevant subdivision is that between internal open innovation and external open innovation. People often make the mistake that internal and external open innovation are mutually exclusive, but they are not.

What is internal open innovation

Internal open innovation (sometimes also referred to as intracompany open innovation) is the first step away from the traditional closed innovation model. Instead of confining innovation to the R&D department, an internal open innovation approach seeks to engage as many employees as possible in the innovation process. In this way, a much greater diversity of perspectives is considered.

The power of internal open innovation lies in three major advantages. First and most obviously, it allows for a wider sourcing of potential solutions. This is a common advantage of all open innovation approaches, so it is no surprise that it is also a powerful driver of the adoption of internal open innovation.

Secondly and more importantly, the implementation of internal open innovation allows for a wider sourcing of problem statements. This is even more crucial than the first advantage as most projects (innovative or not) fail before they even get started as they fail to properly define and address the exact problem they seek to solve.

Thirdly, internal open innovation allows employers to galvanize their labour force. People have a strong need to feel valued, to be trusted and to have the ability to develop their own talents abilities. A great indirect benefit of open internal innovation then, is that when properly run, it allows employees to meet these needs and increase their performance, job satisfaction and lower employee turnover.

External open innovation

Companies that employ external open innovation go a step further. These companies work together with external parties for example dedicated innovation firms, research bureaus, consulting services and universities but also suppliers, customers and in some cases even competitors or the general audience.

To further narrow down the scope of the partnerships’ companies are willing to engage in, various subcategories have been created to help specify the types of external open innovation partnerships out there. The main difference between the various categories is the level of transparency organizations are willing to engage in.

For the categories with the greatest target audience, the shared information tends to be less sensitive in nature and the need to have a specific expertise to weigh in the lowest. These tendencies are not necessarily the right approach however, as breakthroughs can far outweigh any risks related to transparency. Not to mention that often times it is very difficult to determine which information is truly sensitive and which expertise would truly be of service in the quest for a solution towards the innovation challenge the company in question is seeking to resolve.

The most important subcategories of external open innovation are:

- Intercompany

- For experts

- Open to the public

In the subcategory “Intercompany”, knowledge is shared between various partner organizations who collaborate to solve a given problem. Each of the collaborating organizations possesses a piece of the puzzle and the goal is to unite so that the full picture can be unlocked. This type of collaboration works exceedingly well when the relationships between the participating companies are symbiotic in nature (e.g. when they are active in distinct areas of the supply chain for a good or service) and each participant is secure in their added value.

The “for experts” subcategory then, refers to partnerships in which the target group is limited towards a specific group of professionals. If the problem in question is highly complex or technical, it might require the help of dedicated researchers and specialists to be solved. Collaborations with universities or research institutes are often set up when this type of external open innovation is needed.

The last subcategory of external open innovation is labelled as “open to the public” because the organizations using this are open to ideas from the general population. Everyone, regardless of expertise or demographic characteristics is invited to get involved. The most famous incarnation of this type of external open innovation can be found in the form of the open innovation challenges of companies like Agorize but also the crowdsourcing of ideas as in our Boaty McBoatface example can be categorized as a publicly open form of external open innovation.

The main advantages of this approach are mostly the same as the ones we have already touched upon in the paragraphs about internal open innovation. The direct benefits of such an approach are twofold in the sense that they again allow for a wider sourcing of solutions and problem statements, allowing companies to use niche specialities that they could otherwise not afford to consult.

Indirectly, there is again the benefit of increased proximity and trust within a well-oiled external open innovation ecosystem. For example, if companies are proactively solving problems for their most valued customers, these customers will experience far better service and therefore be more willing to purchase more or different services than before.

While companies that rely on external open innovation usually also engage in internal open innovation, that does not necessarily need to be the case. It is perfectly possible for a company to bet heavily on external open innovation while focussing their internal innovation efforts in a single, traditional R&D department.

Example of open innovation at Nokia

A good example here comes from Finnish telecom giant Nokia. The company first rose to prominence as a manufacturer of mobile devices. Unfortunately, after leading the pack in this field for many years and building up an internal research division of 1300 people, the beginning of the smartphone era turned out to be very bruising for Nokia. It made several wrong bets and, in the end, found that it was being surpassed by many of its rivals on all fronts.

Drastic measures were needed to give the company a new lease on life. The management at the time adopted a radical way forward. It sold the mobile device part of the business that had made the brand famous around the world and instead decided to place great bets on IoT, 5G and other telecom technologies. After the sale, the internal R&D team went down from 1300 to 80 people, although numbers rose fast after Nokia used the money from the sale to acquire the hallowed Bell Labs in New Jersey.

Bell Labs and what little remained of Nokia’s original research department would serve as the linchpin in a new open innovation network that would see Nokia work together with external parties to create value for itself. Over the years, a number of initiatives has been launched with the cooperation of several partners.

The five most important of these are the Nokia Veturi programme, the open ecosystem network, Invent with Nokia, the various Nokia Garages and NGP Capital. With the exception of NGP Capital, which functions much like the Unilever Ventures initiative discussed in the section on inbound open innovation, all of these initiatives will be discussed briefly in the next paragraphs.

In the Veturi programme, Nokia collaborates with governmental entity Business Finland to boost both its own Finnish R&D expenditure and that of its partners to help Finland reach the targeted four percent of GDP spent on R&D in Finland by 2030. This ambitious programme, funded with money from the European union sees Nokia partner with partners across Finland to reach the ambitious target. By taking on a leading role in this programme, Nokia secures heavy government support, additional funding for itself and a way to strengthen its partnerships in its home market.

The open ecosystem network is less geographically restricted. It is a free-to-use open innovation platform set up by Nokia and focussed on fostering links between companies of all sizes and individuals of all walks of life to share their real-life problems, insights, assets, and innovative solutions. While it is mostly focused on connectivity, Nokia has stated that it would like to extend the platform towards areas outside of Nokia’s core focus as they believe that turning their platform in a hub with overlapping open innovation ecosystems would pay the most dividends. Invent with Nokia is a fairly similar initiative, although it is a lot more focussed since it specifically targets inventors who can submit ideas for review by Nokia’s researchers. A process that allows Nokia to get quickly involved when promising opportunities present themselves, while the inventors benefit from the feedback the expert scientists at Nokia are able to give.

Nokia has furthermore also created variety of hubs called the Nokia Garages. The Garages are meant to serve as physical gathering points for innovators, a sort of bricks-and-mortar complement to the open ecosystem network discussed in the previous paragraph. In these Garages, employees from Nokia as well as invited collaborators can innovate and tinker without pressure. There are no directives, regulations or other demands coming from the company. Apart from the occasional event organized to focus people in a particular direction, no company intervention is intended so as to empower people to develop their wildest ideas into a reality.

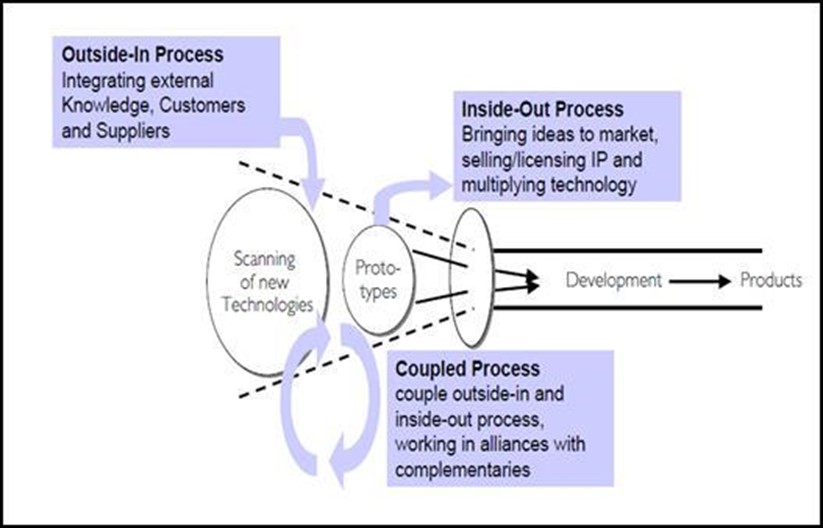

The differences between Inbound, Outbound and Coupled Open Innovation

The subdivision inbound/outbound/Coupled open innovation is often used interchangeably with the internal/external subdivision described above. Unfortunately, this in incorrect and the cause of much confusion as both subdivisions differ in focus.

The internal/external subdivision essentially focusses on who participates in the innovation process. It is therefore used to describe differences in approach between various organizations. The inbound/outbound subdivision on the other hand, was conceptualized to study the direction of the open innovation strategy of a company.

What is Outbound Open Innovation

Companies engage in outbound open innovation when they transfer innovations (be these tools, technology, processes, or anything else that creates competitive advantage) outside of their enterprise. There are many reasons why organizations choose to do this, but it is usually done because organizations believe that the business model of the receiving organization has a greater chance at successfully commercializing the technology.

The most expedient example of this belief is the out licensing of IP and technology to third parties in exchange for payment. The pharmaceutical industry, with its ruthless portfolio management strategies provides us with many use cases for this type of arrangement. Given the vast sums involved in the development of new treatment options and the huge costs in bringing these to market, Big Pharma needs to focus its resources on certain focal areas (e.g., Degenerative Nerve Diseases) to ensure that results are achieved

The open innovation example of Pfizer

It often happens however, that pharmaceutical companies bump into compounds or treatments that might be interesting for diseases outside of their core area of expertise. A popular option for not letting good work go to waste is to out license the discovered compound to a third-party player with a greater fit with the product.

A good recent example of this is Pfizer’s decision to out-license two potential treatments for cancer to Pyxis Oncology. In exchange for the deal, Pfizer received an upfront payment, as well as an equity stake in Pyxis Oncology and the promise of future pay-outs if certain targets are met.

Aside from out licensing, many other forms of Outbound Open Innovation exist such as spin-offs, spinouts, carve outs, split offs and so on. Some of these will be discussed more in depth in the “How to Set Up an Open Innovation” programme section.

The open innovation example of Tesla

One last example of a peculiar kind of outbound open innovation comes from the waiving of IP rights. This is a strategy that has recently been popularized by companies like Tesla and Panasonic, which have recently (partly) adopted such an open-source approach. The later in the field op IoT and the former in the field of electric vehicles.

In Elon Musk’s now famous 2014 post on the Tesla blog called All Our Patent Are Belong To You, he gave the following reason for embracing the open source movement and releasing the patents Tesla had accumulated up until then:

“We believe that Tesla, other companies making electric cars, and the world would all benefit from a common, rapidly evolving technology platform.“

This seems to be an incredibly noble statement of intent, but as always, there is more to this than meets the eye. In the modern economy, platforms have become incredibly important. They act as powerbrokers between buyers and sellers, leveraging the power of network effects to devastating effects against competitors.

One of the reasons why a company could therefore choose to waive its IP right might therefore be exactly to set the standards in a particular field. If everyone else builds further upon innovations initially set by your own firm, there is much opportunity to be mined from the fact that as the original innovator, the firm waiving its IP rights has a huge advantage in capturing the added value that is created. Something we suspect Mr. Musk to know all too well.

The open innovation example of McLean

An incredibly successful example of this strategy can be found in the creation of the standardized shipping container. The idea of containerizing goods was far from new, but only in 1956 did the quiet revolution begin that would power much of the economic growth of the past half century. It is at that moment that Malcolm McLean, an American captain-of-industry decided to waive the patents he had held on to the design of container that was easy to stack and transport.

Before the advent of the modern standardized shipping container, goods were shipped in satchels, wooden barrels and crate that had to be moved around by legions of longshoremen. The process was not standardized at all, prone to disruptions and theft. All of which were quite memorably depicted in the classic film On the Waterfront starring Marlon Brando.

Many people had tried to improve the inefficient transport of goods by ship before, yet none had succeeded because no one had been willing to share their designs. Their existed a plethora of different containers before Malcolm McLean came along, but because every firm stuck to its own designs, no real gains were achieved. Quite the opposite as the various designs made an already dismal mode of transport even more complex.

After Malcolm McLean shared his IP, the true potential of containers quickly came to fruition. Due to their uniform design, they could be easily stacked on top of each other. (Un)loading would also be standardized as everyone could tweak their machinery and procedures around one design. This lead to huge savings on labour costs, better protection against theft and unexpected benefits like lower insurance fees.

All in all, it is estimated that containerization increased bilateral trade by a whopping 790% over 20 years, thus vastly increasing the amount of value that was created. The world thus enjoyed great benefits from McLean’s clever stratagem and the man itself did not do too poorly for himself either. In 1996 he sold his share in Sea-Land, the container business he had created and turned into the biggest global shipper of its day. That deal netted him a cool 160 million USD, which came on top of the fortune he had already build for himself throughout the years.

What is Inbound Open Innovation

For inbound open innovation the direction of the knowledge transfer is reversed. Companies are said to employ inbound open innovation when they acquire external innovations to be implemented in their own operations. Sourcing innovations elsewhere is done to either accelerate internal innovation efforts or to expand the market for the external use of innovation.

Research seems to suggest that many more firms are open to inbound innovation than outbound innovation, so for organizations that are just beginning to contemplate new innovation practices, it might be relevant to start experimenting with Inbound Open Innovation first.

To enable the successful implementation of Inbound Open Innovation, three elements need to be brought together for the perfect mixture. The first important element that needs to be brought into the mix is the adoption of a clear strategic direction. Unambiguous statements of intent from top management are crucial here, as their sponsorship and commitment of the Open Innovation approach will help assuage the fear of people that external innovations do not pose a threat to existing jobs.

The second element is the scanning of the external environment for clues to identify, select, utilize, and integrate new findings. An important but often overlooked aspect successful open innovation efforts, organizations ignore this part of the process at their own peril. Without a proactive search strategy based on the clear strategic directives discussed in the previous paragraph, organizations are forced into a purely reactive roll. When such an unfortunate turn of events takes place, organizations will necessarily be bound into follower strategies.

After strategic directives have been set and the discovery phase has delivered a first clutch of promising solution, the third and final element needs to be added to the mix. All the discovered solutions must now be integrated into the organization. This requires a lot of absorptive capacity and a clear change management strategy that is consistently and conscientiously executed.

There are many methodologies available to guide an organizations’ search for greener innovation pastures (e.g. technology sourcing, in-licensing, working together with innovation studios, etc.). The best way to understand how these can make a difference is by looking at a case study in which some of these techniques were successfully implemented.

The example of open innovation at P&G

One of the most striking examples in this area comes from P&G. They implemented a new programme called Connect+Develop in the early 2000s after realizing that the old-fashioned organization of their R&D efforts was not contributing enough to top line growth.

The increasing complexity of the world and the rapid pace of technological progress had created an environment in which P&G’s costs for R&D were rising, but the marginal gains were diminishing rapidly. The internal R&D department was no longer able to help the company meet its targets on its own. After suffering a huge drop in stock market value, P&G gained the courage to radically change their approach. Instead of the traditional invention model, in which the bulk of innovations is be sourced from within the organization, they decided to make a solution search outside of P&G integral to their whole innovation process.

For any given problem P&G would seek to innovate its way out off, R&D staff were instructed to first search outside of their department, but within the wider P&G organization itself for a solution. In many companies, resources are not allocated efficiently because teams from various departments are working on similar problems without coordinating their efforts. If nothing is found searching internally, the R&D staff would then broaden the scope of their search to determine whether research being done at other companies, universities or any of the other innovation hubs could provide the silver bullet needed to solve their challenges. Only if these steps proved fruitless would P&G seek to develop a solution from scratch. That way, their internal researchers would only be brought to bear on the problems that really mattered, instead of wasting money on developing new solutions where other methods already exist.

This approach was then tested first in a couple of limited trials. The success rate, which was better than results on comparative projects which had solely relied on the old invention model, convinced top management of the viability of their new open innovation model. For the companywide implementation of their program, the exco started by setting an incredibly ambitious target for P&G. Fifty percent of the new innovations it wanted to implement would be sourced from outside of the company from then on. Due to the strong exco support of this target and the fact that this support was broadly communicated throughout the entirety of the organization, concerns about job loss and gradually atrophying internal capabilities were assuaged.

To further ingrain the open attitude, steps were also taken to adjust the internal reward systems of P&G. From then on, top management made it clear that they did not care where the solution hailed from. If an idea turned out successful in the market, rewards for the teams and individuals involved would be the same regardless of whether it was an external, internal, or mixed development.

Now that P&G’s top management had set the scene, it was time to create a comprehensive body of procedures and guidelines to identify the right problems and attract the right solutions to reach the ambitious targets P&G had set for itself.

For P&G, it was quickly decided to adopt two general rules about where and how to search. The first rule was that ideas sourced outside of the company would already need to have gained some traction. This could come in the form of working products, prototypes or demonstrated consumer interest. Furthermore, as a second rule it was decided that these ideas needed to benefit from the capabilities that P&G itself could bring to the table. With these two general rules in the back of their mind, the strategists at P&G started to plot the organization’s new course.

Since a behemoth like P&G is active in so many different fields, there is a vast array of potential areas for it to innovate in. To maximize P&G’s return on investment, it was decided that innovation would be focused based on the results of an extensive needs analysis. At P&G, this analysis was build around three core tenets.

First, P&G started a companywide effort to determine the ten most pressing customer needs that if addressed, would help drive growth at their brands. This is done first at the level of the individual business that together make up P&G, and then all these lists are weighed against each other to create a top ten for the company as a whole. These needs lists are then given over to the company scientists to be transformed into clear scientific problem statements. This often results in elaborate technical briefings which can be send out to partners around the globe who can then help source solutions.

Secondly, P&G also requires its various businesses to put work into identifying adjacencies. These are new products or services that are related to existing products offered by P&G. The idea here is that P&G’s brand power, marketing acumen and other skills build by offering the related product could allow for the new products to piggyback on the strength of the existing products’ standing with consumers.

Thirdly, P&G has chosen to institute a regular cycle of technology game boards. This is a gamified planning tool that allows P&G management to assess the ripple effect caused by the insourcing of new innovations into the company. As each acquisition changes the innovation landscape within P&G, this approach allows management to stay on top of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses. If a particular weakness is identified after a technology game board review, the search can be started to find a patch for it. Conversely, if the game board identifies a core strength, the search can be geared towards finding other ways to boost the innovation’s performance even further. This process can also provide an answer to difficult questions about outbound innovation, like which proprietary technologies to out license, spin off or codevelop with external parties to maximize return on investment on it.

The results of all this analytical work would be brought together and passed on to the various networks in which P&G participates. The company’s directive on this front is quite clear, within the boundaries defined by the need’s lists, adjacency maps and technology game boards everything is fair game. P&G is open to work with anyone from the usual suspects like academic institutions and government labs to individual inventors, venture capitalists, start-ups, suppliers, competitors and so on. Due to the fact that P&G is a massive corporation, it also had the resources to build several proprietary networks. For example, they build a series of connect and develop hubs around the world which are strongly rooted in their local context. The goal of these hubs is to focus on the core strength of the various regions they are in, as well as to discover new products and services that their markets would respond positively towards.

This is only part of the equation, however. P&G also participates in other open innovation networks (e.g. NineSigma, InnoCentive, Yet2.com, etc.), so even companies without the resources to build a proprietary network can be reassured that open innovation holds opportunities for their enterprises.

Another company that is following a similar playbook to P&G is Unilever. One big difference between the two firms is that Unilever, through its 2014 flagship The Foundry initiative, puts an even greater emphasis on attracting start-ups with capabilities to help Unilever steal a march on its competitors. The idea was for Unilever to get involved directly with new companies in need of fresh capital and expertise to market their products. The idea behind The Foundry was to attract these fledgling companies with marketing support, financial rewards in case their solutions help Unilever meet some of its identified needs and access to Unilever Ventures, which could provide successful applicants with the capital required to build a profitable large-scale business.

Coupled Open Innovation

Coupled open innovation then, is the combination of Inbound and Outbound Open Innovation. Organizations engage in coupled open innovation when the flow of knowledge is a bidirectional process (i.e., when an organization both imports and exports innovations.

As can be inferred from its name, coupled innovation involves close integration and commitment to co-creative processes to work as intended. The giving and taking of knowledge is essential to achieve innovations that add value, but the interactivity that this entails soaks up time and resources. Organizations wishing to leverage coupled open innovation will therefore have to have a longer investment horizon than organizations that opt for the comparatively simpler forms of Inbound or Outbound open innovation.

This is mainly the result of what the research literature has dubbed the paradox of openness. Especially in a corporate context, innovation involves two main challenges. First, innovations must be created. This is a challenge that all players in the field of innovation (be these companies, universities or otherwise) face and it is here that openness can have its biggest impact. It is much easier to create innovative solutions in a process of co-creation, particularly in the highly complex world we live in and where many different types of insights need to be combined to create a functioning product or service.

The second challenge, however, is fundamentally different in nature. After coming up with an innovation, companies also need to commercialize them. This usually requires a completely different skillset. It is in this phase of the endeavour that openness is perceived as detrimental, as commercialization in the traditional mindset cannot be done without protection (e.g. in the formalized form of patents or the informal use of trade secrets).

While there are many organizations nowadays buck this traditional mindset, it is understandable that a lot of more traditional companies get cold feet at this point in the process. Not everything can function like GitHub or Wikipedia, where everyone is free to add and use to the resources developed by the vibrant communities that provide the content on these platforms.

With the right legal frameworks in place however, there is no reason to introduce a binary divide between the traditional patent-driven method and the open-repository approach employed by GitHub and Wikipedia. It is perfectly possible to harness the power op open innovation to boost the creation phase and then deploy more traditional techniques for the commercialization of the innovations that came out of the open innovation efforts.

The maintaining of these frameworks and the relationships that they are meant to regulate and protect does require constant attention. It will endure throughout the entire give and take process inherent to coupled open innovation.

Before embarking on coupled open innovation, it is therefore important to assess the absorptive capacity of your organization and in case this is found lacking, to remedy this problem before actively engaging in the coupled innovation process. To do this, new organizational practices must be set up to handle the external knowledge coming in (acquire and assimilate) and the internal knowledge going out (disseminate, monitor, and improve).

While this seems scary, it is not that different from how successful companies handle traditional outsourcing or decide how to deploy freelancers alongside internal teams. Clear stratagems and rules are an essential ingredient for success, we shall therefore discuss this at length in the section on how to set up an open innovation programme.

The example of Coupled open innovation at Intel

A good illustrative example of a firm that has successfully engaged in Coupled Open Innovation is Intel Corp. Their Components Research Laboratory in Oregon was set up to connect the company with the outside world. The firm has acknowledged that linking their corporate practices with outside researchers has cost a lot of work, mainly to improve the speed of transferring promising research results from outside researchers into the organization. Their determination has however created great dividends, as since its inception, the Components Research Laboratory has helped introduce revolutionary technologies such as High-K metal gate technology, Tri-gate 3D transistors, strained silicon, embedded multi-die interconnect bridge (EMIB) package technology, extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) technology and more.

Why do we need Open Innovation?

Now that we have defined Open Innovation, it is time for us to zoom in more on what matters most to our clients, namely the advantages and disadvantages of implementing an Open Innovation programme.

Advantages of Open Innovation

Open Innovation helps these companies beat their competitors by allowing them to be flexible in their innovation practices. Companies adopting an open innovation mindset recognize that not every valuable perspective can be insourced. In other words, there are many smart people outside of the enterprise whose insights could unlock value.

This insight does not mean that the firm itself should stop innovating. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of successful firms in the modern era is that they never stop investing in innovation. Rather, the implication of all of this is that internal R&D efforts should be reconfigured so that it is capable to harvest as much of these outside insights as possible. Creative firms have found a myriad of ways to do so.

Successful examples include Lego, L’Oréal, and Philips, which have all reaped the benefit of the Open Innovation approach but who have gone about it in very different ways. Lego is most famous within the field of Open Innovation for having pioneered the Lego Ideas initiative, which allows it to crowdsource new product ideas from its fans, thus ensuring that they are never out-of-touch with consumer demands. The longevity and success of the platform is often held up as the poster child for publicly open inbound open innovation.

The examples of Lego, L’Oréal, and Philips

Philips flagship initiative on the other hand involved opening a High Technology Campus in Eindhoven (HTCE). On this campus, Philips had centralized its traditional R&D activities since 1964. The watershed occurred when Philips opened up the doors of its HTCE to outsiders. Universities, innovative start-ups and traditional companies flocked to the HTCE’s spacious campus and turned Eindhoven into a powerful innovation hub. The HTCE nowadays describes itself as the smartest square kilometre in Europe and is able to back up that claim by pointing to the 235 innovative companies that are a part of its ecosystem.

Compared to Philips and Lego, L’Oréal is a relative newcomer to the scene of Open Innovation. This has allowed it to benefit from wisdom build up by others over the years and to plug in its own investments into pre-existing accelerators and incubators. One good example is L’Oréal’s participation in the Parisian Station F, the largest start-up campus in the world, where it is responsible for the exclusive beauty tech accelerator. While the achievements of L’Oréal are not to be discounted, it is a good example to include here as it shows that companies do not need to invent the wheel when it comes to Open Innovation. There are recipes for success and existing initiatives that have gained traction. As part of any Open Innovation strategy, it is worthwhile to look at what is already out there before inventing your own Open Innovation accelerator from scratch.

What the three examples above illustrate is that Open Innovation can take many different forms and process many different types of inputs. It can be laser-focused on one particular group (e.g., Lego and its hardcore fan base), but it can also be expansive, taking in a lot of different stakeholders ranging from individual creatives to large institutions, suppliers and customers to competitors.

By banding together in this type of Open Innovation ecosystem, the pace of discovery can be quickened. However, the advantages of Open Innovation do not end there. In many sectors, innovation has become an incredibly expensive endeavour. While there are still inventors tinkering around in their garage boxes, most inventions and scientific breakthroughs today are made by groups of researchers working together. Moreover, these groups usually use a lot of expensive equipment.

The capex requirements this entail might prove too much for the individual enterprise, but combined with the resources of others, the sort of R&D investment needed to produce a breakthrough and then commercializing it no longer looks infeasible.

This is a crucial advantage of the Open Innovation approach, as it also allows companies to get involved earlier in the value chain and fund their own basic research in the long run. This has the added advantage of mitigating risk for companies. On their own they cannot commit to every possible innovative idea, but the impact of missing out on the next big thing is a terrifying prospect (as exemplified by the rat race of companies investing in e.g. the meta verse or EV’s). By working together with others, an individual organization can put its finger in many more pies and thus it can ensure that finds itself on the winning side of history when the next technological breakthrough arrives on the scene.

Disadvantages of Open Innovation

There is no such thing as a free lunch, as Nobel prize winning economist Milton Friedman already pointed out in the title of his eponymous book from 1975. While the drawbacks of Open Innovation do not necessarily outweigh the advantages of the system, it is important to be mindful of them. After all, it is only by recognizing risks that mitigating actions can be identified and afterwards successfully deployed.

For the first obvious disadvantage, we only have to point to the curious case of Boaty McBoatface with which we started this introductory article. Opening up your innovation practice to outsiders entails giving up some degree of control over (the outcome of) your innovation process.

Therefore, it is paramount never to embark on an Open Innovation journey without carefully considering the scope, scale and implications for the rest of the business. Luckily enough, the right set of constraints actually enhance creativity (perhaps a topic for another article in the future). If done right, the outcome of your Open Innovation journey would therefore not be adversely affected.

Another potential pitfall with Open Innovation is the so-called flight of knowledge. While we live in an age that – on the economic front at least – favours connectivity, interoperability, and the free exchange of ideas, few would argue that keeping certain technical or commercial information hidden is an unwise move.

Striking a right balance between divulging certain trade secrets and maintaining competitive advantage is one of the more challenging balancing acts an organization faces when seeking to operate in an Open Innovation paradigm. Ultimately, this is a matter of Strategy and any decision here should be made based on strong factual assessments of the business environment.

How to implement Open Innovation?

What is an open innovation strategy?

To answer this deceptively simple question, we first need to clarify the question. We do this by breaking the questions down to first principles. Using that approach, our quest starts by finding an appropriate description for strategy.

The earliest definition of strategy to have had great impact is the one written by Prussian general Carl Von Clausewitz in his classic 1832 work Vom Kriege (On War). In it, he defined strategy as:

“the use of the engagement to attain the object of war.”

This definition is rather bellicose, as it reflects the military context from which it hails. Nevertheless, Von Clausewitz’ work definitely serves as the beginning of serious thought about strategy in the western canon and influenced later descriptions like that of the Strategic Thinking Institute have defined strategy in a business context as follows:

“Strategy is the intelligent allocation of resources through a unique system of activities to achieve a goal.”

While more modern definitions are more accurate, as well as better contextualized to the business context on which this article focusses, the older definition by Von Clausewitz rooted into war hints at a fundamental truth about strategy. It is not something that you want to get wrong as an organization or individual.

When strategy fails, it can threaten the very existence of companies. While there are phoenix stories, like for example the Nokia case study discussed in the section on external open innovation, these tend to be exceedingly rare.

In this, strategy fundamentally differs from innovation. Where failure is anathema to strategy, it is the bread and butter of innovation efforts. Although we would like to have a 100% failproof way of delivering both radical and incremental innovation, the truth is there is none. To win big, organizations must be willing to take risks. That is great when bets pay off, but inevitably some will not. The goal for these unfortunate failures of course, is to always fail forward and to chip away at our organizations’ problems one step at a time.

If strategy and innovation differ so fundamentally, how can both concepts be brought together into a comprehensive whole? That requires some flexibility as both concepts need to be applied less rigidly than most people would like.

Good innovation strategies commit to an innovation mission that is shared throughout the entire company and is of course meant to sustain the organization’s future prosperity. This is different from the more discrete goals that are advanced by the company (or business unit’s) overall strategy. Innovation strategies should be as succinct and elegant as possible, as they should not stifle creativity. In this regard, the golden standard is set by Apple with its devilishly simple, yet expansive purpose off:

“creating products that enrich people’s daily lives.”

The innovation strategy begins with that common goal and should then further define the key activities envisioned to bring that common goal within reach. This includes taking decision on the openness of the organizations’ innovation practice to input from and collaboration with actors outside of the company, as well as decisions on the degree of experimentation allowed and the autonomy of staff to pursue innovation efforts without oversight from senior management.

The resulting strategy should be broadly disseminated amongst the companies’ innovators. For companies that choose to implement an internal open innovation process, this should be scaled up to include all the employees within the company. If external open innovation is also on the cards, the organization should also assemble a communication plan for dedicated groups of outsiders (e.g. external technology entrepreneurs or suppliers) and disseminate the relevant parts of the innovation strategy to these groups.

It is very important at this stage for senior management to step in and show dedicated support for innovation within the firm. Sponsorship Is one of the most important enablers of positive and lasting organization change, so the innovation strategy must be seen to have the support of everyone in management. That way, understanding of both the inevitability and the importance of the innovation strategy to the organization’s future success will trickle down until it permeates the entire organizational structure. When all the people who could potentially be involved in the process know and understand the organization’s innovation strategy, it becomes actionable, and the company can get to work.

The example of open innovation at Netflix

That good innovation strategies do not necessarily have to be ultracomplex is illustrated by the example of Netflix. According to Netflix’ CEO Reed Hastings, if the culture is right, strategy can be incredibly easy. At Netflix, the innovation strategy is built on four core principles and meant to help Netflix reach its desired goal of entertaining the world.

The first is called farming for dissent. Whenever someone comes up with a new idea, they are expected to present this to their peers. These peers are then asked to give their opinion. Netflix has a very assertive culture, and this principle is the clearest expression of that. In case employees disagree with any given proposal, they are expected to vocalize their opinion. While this is no panacea to all ills and there are questions to be asked by the impact of this policy on more introverted team members, it does suss out problems sooner rather than later. In that regard, this Netflix stratagem is not that different from Apple’s emphasis on collaborative debate which we shall discuss in the section on how to implement an open innovation programme.

The second principle is the importance of experimentation. Experimentation lies at the heart of any innovative organization, but Netflix goes above and beyond this by not setting any limitations on the experimentation process. There are no gatekeepers, so if someone believes something should be tested, they can take the initiative to do so even if their superiors are against it. By doing this, Netflix cuts through a lot of red tape, and speeds up the innovation process dramatically.

The third principle is the role of informed captains. Netflix likes to devolve authority to lowest ranked person capable of making a decision. Instead of governing by committee, Netflix allows individual employees to take on decision-making responsibility. Each of the captains is expected to listen to other people’s opinion and feedback on their project, but ultimately, it is only the informed captain who gets to decide.

The fourth and final principle is one of accountability. It is important for Netflix to wind down initiatives that underperform as quickly as possible. While success is to be celebrated, failed projects are not necessarily seen as a cause for alarm. After all, they provide excellent learning opportunities to help avoid similar mistakes in the future. An informed captain who notices that one of their calls is turning sour is therefore expected to intervene immediately. This helps the company move forward at breakneck speed.

What is an open innovation platform?

Open Innovation platforms are a tool meant to help organizations simultaneously streamline the open innovation process and lower the barriers of entry for outsiders to get involved with solving the companies’ problems.

Typically, the Open Innovation platform is meant to be user-friendly, with a core division of the website into certain focal areas underneath which distinct challenges are posted. The level of detail included under the challenge will depend on the sensitivity of the project and the target audience. Challenges open to highly specialized individuals will typically include more details than challenges aimed at a wider audience.

While not necessarily the case, the platform is often intended to facilitate at least the earliest stages of the Open Innovation process. It can do this by for example, helping people and organizations-built connections to jointly tackle a challenge, allow for Q&A with company insiders, the submitting of first designs, rating of ideas and so forth.

Open Innovation platforms come in many shapes and sizes. The most important division between the various platforms is that between proprietary and open platforms. The former is dedicated exclusively to one single company, often relying on a push-based approach to attract as many potential solution providers as possible to the party. These types of platforms are mostly custom build for the benefit of the company and are therefore entirely in line with the companies’ internal processes and approach.

The latter on the other hand strive to be as accessible as possible and to foster communities that frequent the platform regularly. These types of platforms stimulate people, teams and organizations to look over the fence and see whether their expertise would also not be in demand in places they had not considered at first. These platforms are built to accommodate many different organizations. Their customization to the recipient partner-organization is therefore low or even non-existent, which might cause issues

The example of open innovation at TotalEnergy

An example of a proprietary platform is the Open@TotalEnergies platform that was created by the eponymous oil major to accelerate ideas that could have an impact on reaching a carbon neutral future. On the platform, TotalEnergies has identified nine core innovation topics (ranging from e.g., oil and gas, to new energies and Industry 4.0.).

For each of these topics, it regularly launches dedicated challenges that are meant to address gaps in TotalEnergies that the company has identified itself. Start-ups with a potential solution are encouraged to apply with the promise of financing, real-life testing, and co-innovation/commercial development opportunities with TotalEnergies’ internal teams.

For a platform open to calls from many different organizations, InnoCentive is a particularly good example. This platform was initially created by employees of the American pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and was later spun-out in a clear example of practice what you preach as this was a solid example of an outbound innovation.

InnoCentive offers organizations roughly two big options. The first is that their platform is offered to the organization’s employees, partners or customers so that these valuable stakeholders get a somewhat customized platform in front of them. The second option then is that InnoCentive presents an organizations’ challenges to a (specialized part of its) network of 380.000 problem solvers. In case a challenge is resolved successfully, cash prizes are usually handed out to the wining team of problem solvers. This can range from the average of 20.000 USD per solved challenge to high awards worth more than 100.000 USD.

While platforms are often part of the Open Innovation mix, they are not essential to implement an Open Innovation strategy. It is always important to think about the goals of your organization’s innovation strategy and based on that decide whether these platforms can be of use. If the answer to that question is positive, the next step is determining what kind of platform would be needed to best answer your organization’s challenge before then looking for a solution in the market.

Best practices to enable open innovation

The most important question that remains is how to effectively implement a consistent and successful open innovation programme. This is a multifaceted challenge and is highly dependent on the sector, organizational culture, and leadership of any given organization.

Despite this, we have compiled a short list of best practices which will help shape the success of your Open Innovation efforts. We will weave in and out of our list with best practices which was compiled based on our own experiences and mixed with insights from scientific research and use cases to help clarify the factors you need to consider maximizing the value added to your organization by your open innovation efforts.

Culture

To begin our list of best practices, we shall begin on the highest level. As management guru Peter Drucker was want of saying that culture eats strategy for breakfast, it stands to reason that we also have to begin with this dimension.

In our experience, which is further supported by the use cases discussed in this article, truly innovative companies always share one important attribute: they are open to debate and everyone’s point-of-view is considered valuable.

This mess of opposing views can be difficult to navigate for more authoritarian managers, however, it is precisely the ever-clashing comparison of opinions that help organizations chart the most profitable path forward.

While the modalities of such an open culture can differ (e.g. Netflix’s culture is famously combative, while a Japanese company like Fujitsu is less assertive), the fundamental thing they all have in common is a high degree of psychological safety.

For an organization to have a high degree of psychological safety, it needs to incentivize curiosity and critical thinking throughout the entirety of the organization. Even the most junior employees need to feel like their contributions are valued and that it is okay to disagree respectfully with both their peers and their supervisors.

Work should be framed as much as possible as a learning problem and people should be given the room to upskill themselves and help others do so as well. The best way to achieve this is to incentivize good behaviour. For a primer on how leading Chinese companies tackle this issue, we are glad to refer you to our article on the DEDA Management philosophy which is currently giving the adhering Chinese firms a competitive edge over their peers.

To start considering work as a learning problem, it is also important to recognize one’s own fallibility. No one is right all the time and when people feel secure enough to openly recognize that fundamental truth, they will be much more open towards owning any mistake. This is critical to help weed out mistakes and underperforming projects, which allows for resources to be allocated far more efficiently.

If your organization has not yet achieved a high-level of psychological safety, then we would advise you not to expend scarce resources on extensive innovation programmes (open or otherwise). While companies without adequate psychological safety can certainly innovate, we can guarantee that they will not do so efficiently. Therefore, it is important to first ensure that psychological safety becomes integral to your organization’s culture, an approach that will pay dividends across all your activities before focussing on trying to germinate an innovation programme in poisonous ground.

If you are curious about the psychological readiness of your organization to embark on its next innovation journey, we warmly recommend using the Morale / Cohesion Matrix. This framework allows for quick and intuitive assessment of your companies’ readiness for complex changes.

Strategy

As mentioned earlier, a good innovation strategy should create a common mission for your organization to rally around. The strategy should be concise, clear, and actionable. Furthermore, it needs to leave room for failure and be communicated to all stakeholders involved in the innovation process.

As part of the strategy, decisions have to be made about what type of open innovation collaborations your organizations want to engage in (internal and/or external) and what the aim of the open innovation effort is (inbound, outbound or coupled).

These decisions should be coupled to fair assessment of your organization’s current absorptive capacity and if necessary, a plan to increase this capability in the future through for example hiring new people, restructuring the organization or utilizing new sources of finance. The absorptive capacity of the enterprise tells you how able the organization is at integrating new innovations into the fabric of everyday life.

This capacity takes both financial and non-financial parameters into account (e.g., availability of staff members) and will determine both the scale of your Open Innovation efforts (e.g. an ambitious fifty percent external innovation like P&G or something a little more modest) and the type of tools you can use. Organizations with lots of financial firepower for instance, will be more able to rely on acquisitions and in-licensing than organizations that need to bootstrap and would be better served by formulas where it only pays for success (e.g., a successfully solved problem posted on one of the many open innovation platforms).

Leadership

Another important aspect to be considered is the leadership given to the people within the organization. Even the best strategies will fail when senior leadership within the organization fail to pull their weight.

Successful organizations have a management that practices what it preaches and leads the way. This in turn inspires people to also pay attention to fostering the culture of psychological safety and will increase the organization’s overall absorptive capacity, as well as streamline the discovery process from where new innovations are sourced.

The example of open innovation at Apple

An interesting case study about the people aspect of innovation comes from Apple. This might be surprising to some readers with a bit more experience in the field, as Apple is not known for being an enthusiastic proponent of the Open Innovation movement.

Apple has contributed more to the Open Innovation paradigm than people realize, in part because a lot of Apple’s strongest work here actually predates the formulation of the concept by prof. Chesbrough. From a very early-stage Apple became a systems integrator. Standardized components were used to build early Apple products like the Apple 1, II and Macintosh before this approach became fashionable. This allowed Apple to focus more of its efforts on the development of its software, which Jobs and Wozniak rightly saw as the most important part of their final product.

A more recent example where Apple turned to the wisdom of the crowds to gain a competitive advantage can be discerned in the history of the App Store. Before the advent of this type of marketplace, it was a pain to get third party software distributed. The App Store and its competitors made this process much easier, which led to a great increase in value for users who could now find a vast range of better apps on their smartphones. Part of this value could be capture by smartphone manufacturers like Apple, as users were more easily swayed to pay a premium for their phones.

The two examples above notwithstanding, it is true that Apple’s openness in the present day leaves some things to be desired. Where they do succeed in (and that admirably so) is how they manage their people into wrangling every bit of value out of the innovation process. It is in this that their example merits further study.

To begin to understand Apple’s success at managing the innovative potential of their employees, we need to start with its organizational structure. While Apple is now the largest company in the world by market value, it has resisted the temptation of adopting the typical multidivisional organizational model favoured by large multinational corporations and instead has opted to remain organised as a functional organization.

- Functional organization: The company is divided into parts based on areas of functional expertise (e.g. sales or operations)

- Multidivisional organization: The company is divided into parts based on the completion of specific tasks and/or the management of operations within a single region [e.g. General Electric’s product divisions like Aviation and Healthcare or PepsiCo’s geographically distributed business units like North America Beverages (NAB) Quaker Foods North America, Latin America, Europe Sub-Saharan Africa (ESSA)]

To begin to understand Apple’s success at managing the innovative potential of their employees, we need to start with its organizational structure. While Apple is now the largest company in the world by market value, it has resisted the temptation of adopting the typical multidivisional organizational model favoured by large multinational corporations and instead has opted to remain organised as a functional organization.

This was not always the case. Before Steve Jobs triumphant return, the poorly performing company was managed in the traditional multidivisional way with separate business units run by general managers responsible for their own P&L’s. Jobs did not believe in this organizational model and faulted it for Apple’s rubbish performance as an innovator in the years of his absence.

He therefore decided that the general managers had to go. Instead, he would reinstate a functional organisational structure. One that would remain in place (with some new functional areas added over the years) throughout both his tenure as CEO and that of Tim Cook, his even more successful successor. All of this despite the fact that Apple multiplied its revenue fortyfold since then. Now, we certainly do not want to claim that the functional organizational model in itself was enough to create the innovation colossus that Apple is today. If that was the case, many more firms would be dazzling us with such a deluge of great new products and services that we would simply be swept away by it. Far more important were the steps taken after the institution of this functional model.

The first and most important of this is that Jobs wanted Apple to celebrate its experts. He famously stated that Apple only hired the very best, which is something a lot of Fortune 500 companies claim and none of the others could lay claim to such a vaunted performance as Apple has had over the past decade. Some might argue that this simply meant that Jobs was actually right, but we believe that it was more a case of hiring excellent (though not necessarily the best) people who were then lead in a way that made the actual difference.

We have already talked about the importance of having a clear strategy for (open) innovation efforts. Apple’s states elegantly that its raison d’être is that it is in the business of creating products that enrich people’s daily lives. We will not discuss it in depth here but suffice to say that this (and Apple’s other strategic directives) give a clear direction to the companies’ efforts.

The 3 building blocks of open innovation at Apple

On top of this strong sense of purpose, Apple has built its innovative efforts on three core building blocks. The first is deep expertise. The late Jobs believed strongly that it was easier to turn functional experts into good managers than good managers into functional experts. While there is something to be said for this vision, it is not something that is necessarily true (or at least not true all the time). What is important in this approach, however, is that it empowers the people with the right knowledge to accurately assess which bets could be truly transformative.

This is also important in the context of open innovation, as the paradigm is certainly not an excuse to outsource innovation to specialized firms. On the contrary, it is precisely the people who are currently doing innovation within the firm that should be empowered to guide the search for solutions outside of the companies’ own premisses. In that way, the best voices within the company are amplified and are able to reach a far greater volume than if locked inside of restrictive boundaries of the traditional invention model.

An added advantage of this lionization of expertise specifically for organizations with a functional organization is the fact that there is a deep bench of specialists to fall back on. All of the experts together create the opportunity for a virtuous cycle of learning as the experts challenge and learn from each other.

A second important building block for Apple’s innovation success is the immersion in details of its managers, which is made possible by the fact that they are all experts themselves. In most organizations, there is a tendency to simplify projects as they climb the hierarchical ladder. At Apple however, managers are encouraged to drill down on the details and to really take their time to probe everything that attracts their attention.

This is an incredibly important part of the innovation process, that is often overlooked by managers in less successful companies. A culture of psychological safety, where employees are empowered to ask question so that together they can improve on projects is essential to success. Not just in innovation efforts but also in other less exciting aspects of running a company.

The third and final building block of Apple’s people strategy for innovation that is edifying for other companies is the spirit of collaborative debate it fosters. This is an extension of fostering the culture of psychological safety that was discussed in the previous paragraph. The highly complex technological landscape that Apple has to navigate often requires collaboration between members of many different teams and their leaders.

In these cases, Apple expects its leaders to simultaneously be partisan enough to fervently defend their own views and open-minded enough to change their views in case the other side of the argument makes a better case. This might seem simple at first, but psychological research has shown that it is actually incredibly hard for people to change their opinion, even when confronted with facts. This is particularly the case when egos are at stake and people are in competition to secure certain spoils (e.g. promotions, etc.) for themselves.

Apple gives a lesson into stimulating this difficult combination of attitudes by having its leaders maintain a deep understanding of and devotion to the company’s values. Guided by that central drive to create outstanding products, the culture of psychological safety fostered through many years of hard work allows for the open debate that is required to unlock the company’s collective intelligence for better decision making.

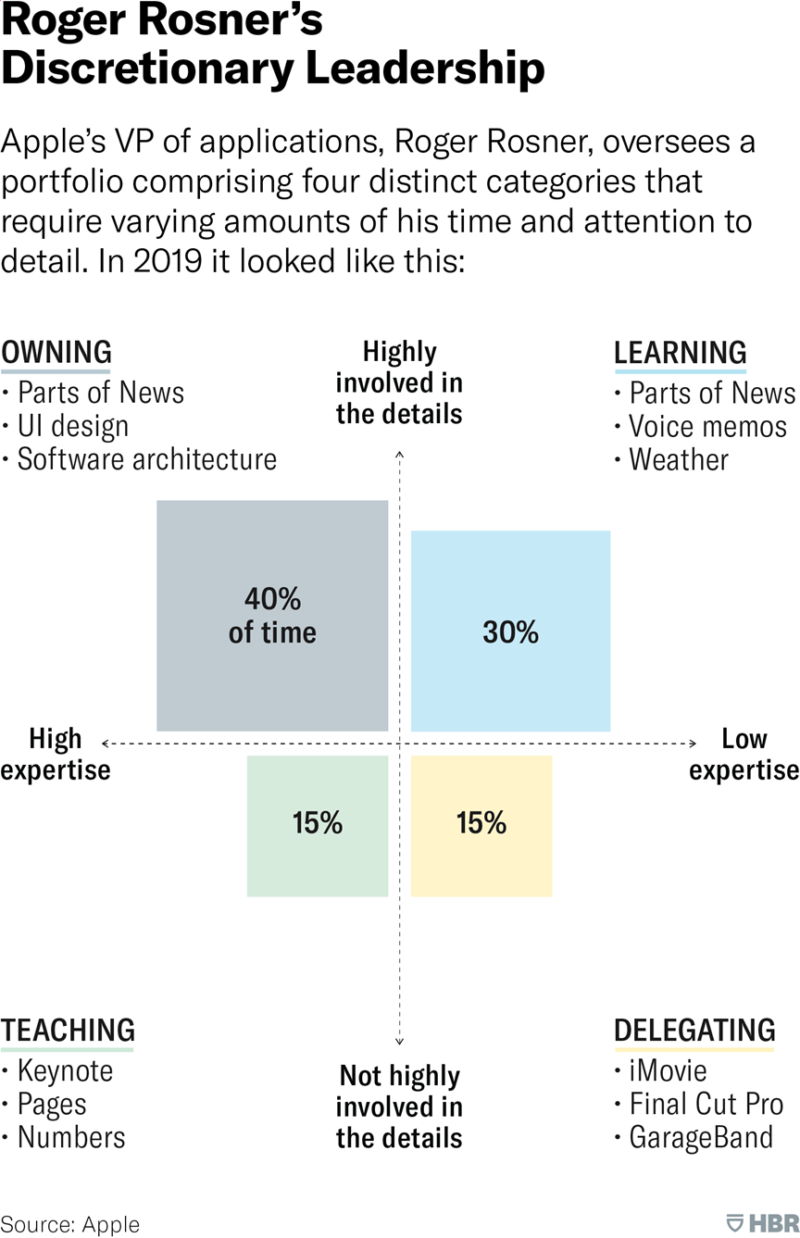

While the above building blocks offer important lessons for companies setting out on their own paths to reap the rewards of open innovation, Apple is not done with its lessons. After all, one important question remains, how can organizations future proof this recipe for success, especially when in periods of growth that keep adding more responsibilities towards management. Some firms respond to this by simply hiring more managers. This can however create a lot of clutter and makes it harder for the necessary quality of leadership to be maintained. Apple then, has sought a solution in what it has called its discretionary leadership model.

This model divides the time of its leaders into four distinct activities based on the level of attention that is required and the depth of expertise possessed by Apple’s leaders. The four dimensions are own, learn, teach and delegate. Under teach and learn we find those activities that require great attention of the leader. The difference between the two dimensions is that activities which are owned are considered to be part of the leader’s core expertise, while activities outside of the leader’s core expertise and for which they need to acquire new knowledge, fall under the learn dimension.

In both cases the leader retains oversight, but Apple insists that their style of questioning the details is adapted towards the dimension the activity finds itself in. In the own and teach category, leaders are expected to question subordinates from a deep reservoir of expertise. When activities are in the learning and delegating dimensions, Apple’s leaders must be more mindful of their own limitations and launch inquiries while being aware of their status as novices to that particular activity.

Activities that fall under the teach and delegate dimension do not require the direct attention of the leader. If these are activities that fall under the leader’s core expertise, they are expected to pass these skills on to others so that they can take over ownership of that activity. Crucially, Apple expects that even its most senior leaders spent time teaching their core skills to their subordinates in the areas that fall under this dimension. In case the leader is not an expert in the activity, they can delegate the task to others who are. This last category is not favored by Apple, as it generally seeks to maintain its expertise driven culture and this category falls more into general management territory.

The discretionary leadership model is an insightful tool that can also be used by other companies to focus their leaders’ efforts on value added tasks. We would therefore recommend applying this tool towards your own innovation efforts, as it allows for increased focus, provides a clear understanding of activities for which staff members could use help, allows them to pass on skills and finally makes it clear which items to delegate.

Experimentation

A commitment to experimentation should be demonstrated by leadership, included in the organization’s strategy, and be embedded in an organization’s cultural DNA. Due to the importance of good experimentation, we decided to mention it separately here even though it is something that should already be presented in all the other dimensions mentioned above.

Experiments have made the modern world. Their transformative power caannot be underestimated, and no modern company can do without them. The aggressive pursuit of experiments to establish as rapidly as possible whether something works or not is essential to good resource allocation.

Of course, experimentation should be done in a correct way to fully leverage the results they produce. To do that, it is important to devise a common roadmap for experimentation. This should decide who has the authority to launch an experiment (we advise to devolve this to as low a level as possible), what methodological steps need to be taken (as a good experiment can be hard, as all professional scientists can attest) and most importantly of all, how results should be documented. Particular care should be taken to ensure that even unsuccessful experiments are documented and made available to other employees in the company. Mistakes are only human, but successful organization ensure that they never make the same mistake twice.

Targets and Renumeration Policy

As part of the companies open innovation strategy, we find it wise to follow the example of P&G and adopt a concrete target for the percentage of innovations sourced from outside of the traditional boundaries of the internal R&D department.

These target, like the strategy, need to be clear, concise, and actionable. What is also important is that they are adequately rewarded. The idea behind open innovation is to focus the efforts of internal researchers only on significantly hard problems for which no off-the-shelf solution is available. If the people identifying problems and solutions are however told that they are evaluated based on the source of the innovation instead of the speed of delivering a solution to a problem the organization is facing, then naturally people will prioritize internal developments even when these are not the most cost-effective or even best response to the challenges faced by the company.

Talent Management